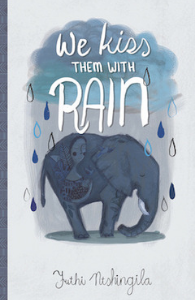

After Sipho’s funeral things became progressively worse for Mvelo and her mother Zola. Mvelo was young, but she felt like an old, worn-out shoe of a girl. She was fourteen with the mind of a forty-year-old. She stopped singing. For her mother’s sake she tried very hard to remain optimistic, but hope felt like a slippery fish in her hands.

They had been in this position before, where someone in the pension payout office had decided to discontinue their social grants. One grant was for her being underage, reared by a 31-year-old single mother; the other was for Zola because of her status.

The thought of having no money for food, to live, drove Mvelo mad. “Why are the grants discontinued? My motheris still not well enough to work,” she demanded from the official with the bloodshot eyes, who was popping pills like peanuts into her mouth. Her bad weave and make-up made her look like a man playing dress-up. It was obvious to everyone in the queue that the official was hung-over.

“Hhabe, hhayi bo ngane ndini, ask someone who cares. You’ll see what it says here: DISCONTINUED. You will have to go to Pretoria where all your documents are processed. Now shoo.” She waved them away. “It is my lunchtime.” The official’s mind was on a cold beer to deal with her hangover.

Zola stopped her daughter from engaging the woman any further. “It won’t help, Mvelo, let’s go back home. We will make a plan.”

They were a sad sight. Zola was a shadow of her former athletic self. Her tall frame made her look even worse than she was. People in the queue gossiped behind their hands as

usual.

The sight of someone obviously sick seemed to excite them to talk about what was no doubt true for many people waiting there, even if you couldn’t see it.

Mvelo and Zola had borrowed money for taxi fare to come to the pension payout hall. Now they would have to walk, and the Durban heat was suffocating. Hot tears stung Mvelo’s eyes; the lump in her throat burned. She drank water and began to navigate through the crowd towards the road, heading back with her fragile mother. And just then an unlikely angel materialized from the queue in the form of maDlamini.

“Mvelo,” she called out to them. For once Mvelo was happy to answer maDlamini’s call. She nearly fainted from a combination of relief, hunger and heat. “They said our grants have been discontinued, and now we have no money to get home.” Tears of anger and hopelessness about their situation kept coming. Cooing, maDlamini comforted them and offered to give them the taxi fare they needed. Her act of kindness was fueled by the attention she was getting from the onlookers in the queue.

It was that day, when her mother’s disability grant was discontinued, that Mvelo stopped thinking any further than a day ahead. At fourteen, the girl who loved singing and laughing stopped seeing color in the world. It became dull and grey to her. She had to think like an adult to keep her mother alive. She was in a very dark place. One day she woke up and decided that school was not for her. What was the point? Once they discovered that her mother couldn’t pay, they would have to chuck her out anyway.

Zola insisted on them going to church even at her weakest. Physically she was weak, but her will to live had not left her. She was not strictly conventional in the ways of the church, though. She prayed differently from other people. When things got too much she would say: “Well, what can I say, Mother of God. We, the forgotten ones, we scrounge the dumps for morsels to sustain us through the day to silence the grumbles in our stomachs. We are armed with the ARVs to face the unending duel with that tireless, faceless enemy who has left many of us motherless. We, the forgotten ones, know that rubbish day is on Mondays.”

“We come out in our numbers on Monday mornings to scrounge in the black bags that hold a weedy line between life and death for us. We search for scraps to line our intestines, shielding them from the corrosive medicines we have to take, lest we die and leave orphans behind. We dive in with our hands and have no concerns for smells of decay. Maggots explore our warm flesh as we dig into the rubbish to save ourselves, to buy time for our children. We live off the bins of the wealthy. Some of them come to the gate, offering us clean leftovers, while others come out to shoo us away. We are the forgotten ones, shack dwellers at the hem of society, the bane of the suburbs. We move from bin to bin, hopeful for anything to buy us time.”

This was Zola’s talk with Jesus’ Mother at the end of a long hot day, while standing in the middle of the shack that she shared with Mvelo, and washing dishes in a bright blue plastic basin.

“Tomorrow is another day for us,” she would say, switching from Mary to Mvelo.

Sometimes Mvelo craved that her mother would just be normal, and wished that she would say “Dear God” at the beginning and “Amen” at the end like other people do. But Mvelo and her mother were not normal, she had come to that realization soon enough.