This Q&A was done by our intern Naomi Valenzuela. Naomi is from Phoenix, Arizona and El Paso, Texas, and is majoring in Creative Writing and minoring in English & American Literature at the University of Texas, El Paso, with plans of working in the publishing business after graduation. You can find other author Q&As here.

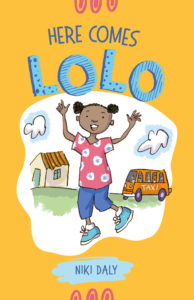

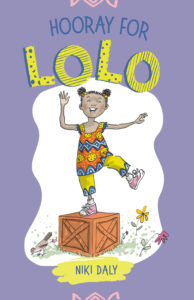

This month, we have not one but two marvelous releases from award-winning author Niki Daly: Here Comes Lolo and Hooray for Lolo. The Lolo series introduces us to Lolo, a generous and artistic South African girl. Lolo always finds adventures, even in the most mundane situations. With her mother and grandmother by her side, Lolo is ready to take on anything. Children will love these stories as Booklist mentions in their review, “With a simply written, graceful text and gray-scale pictures on nearly every page, these appealing stories are just right for children moving from beginning readers to chapter books.”

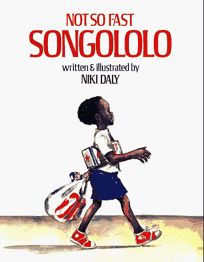

Niki Daly is not only the author, but also the illustrator of these two books. Daly is a South African, author-illustrator, well-known throughout the world with a great number of children’s books written, and several awards won. Some of these books include Not So Fast Songololo, with awards in South Africa and the U.S., and Why the Sun and the Moon Live in the Sky.

In this author Q&A, we talked to Niki about his inspirations when creating Lolo, how his childhood influenced his writing, and his advice for future writers.

When was the moment that you decided you were going to write children’s books?

When I joined the Illustrator’s Association in London in the mid 70’s and met a fellow member, Eliza Trimby. At the time I was a freelance illustrator/designer working mainly for small design companies. Eliza was already illustrating children’s books and had an agent. And through her influence and guidance I wrote and illustrated my first books The Little Girl Who Lived Down the Road in 1978.

Did you always plan on being the illustrator for your books?

Actually, what I didn’t plan, was being the author of my books. But I realized that if I was to get into the field of children’s books that I would have to present an entire project to a publisher as there were far too many great and established illustrators to be able to compete with. But there were far fewer illustrators who could write. And that’s where I scored.

Has your writing process changed throughout the years or throughout books?

I was a songwriter before I started writing children’s stories and have not veered much away from the way I wrote lyrics, in that the words have to sound good on the ear – lyrical in other words. That’s how I test my writing to this day. If it doesn’t sound good on my ear, then I’m dissatisfied with what I have written.

Why did you choose to make your child protagonist a black girl? Did you draw on anyone for inspiration when creating and writing Lolo?

When I returned to South Africa at the beginning of the 80’s I could not recognize the streets in white areas as the streets I grew up in, with kids playing games and hanging around outside. I returned home during the most severe clamp down and oppression by the Apartheid government. Blacks were angry. Whites were scared. Houses in white suburbs were shrouded in security. Compared to the street life I could relate to as a child, I found little that interested me in the subdued streets and middle class culture I found myself in.

So, I turned to the township streets and the lives of the poor and working class to find settings for the stories that I could tell. Because of both the history and lingering effects of the racist system of Apartheid, the social fabric of black communities has been damaged, resulting in a break up of many families, leaving children without the presence of fathers. As a result, a great many families, such as those portrayed in my books, consist of children, mother and grandmother.

Although I have cast boys in quite a few of my books, I am more at ease drawing and projecting onto a little girl. I guess this comes from hanging out more with my sister and her friends than I did with my brother and his wild friends. If you ask me who is Lolo, I say, ‘I am Lolo.’ As a further note, I regret eliminating the father from my pictures families. And I plan to redeem myself by doing a book that celebrates good fathers – a recent realization, having met enough great fathers for me celebrate in picture book and at a time when good men are being tarred with the same brush as those who give my gender a bad name.

What made you decide on the family structure given to Lolo?

More than one child inevitably invites more writing and a shared focus. So, for simplicity sake, I focus on the solitary child – again a situation I strongly identify with. For, despite having a brother and sister, I have always felt alone in the world, having to deal with issues on my own with occasional help of an adult outside of my family. Sadly, I never saw in my parents someone I could turn to. My background is really what informs my stories and the way I write them. I guess that goes for most writers, we write about ourselves.

What are some key themes that you hope readers take from Lolo’s experiences?

Kindness, optimism, hope and humor.

There are some serious topics you discuss within the Lolo Series, one example being animal abuse. How do you go about these topics when writing for children?

I’ve hardly touched on fantasy in my work, although I love folk and fairy stories. But I’m keenly tuned to my surroundings and ALWAYS switched on, so I write about what I see and hear around myself. And I see and hear everything from what is beautiful to what is ugly in the world. But because I am an optimist, I always find a way to make things work for my characters by giving making them resourceful, kind, optimistic, and giving them friends. I also add a dollop of humor into the mix to avoid over seriousness.

What types of books did you enjoy reading as a child?

My family were not readers. In fact, I have no memory of seeing my mother nor father with a book. But I had an older sister who loved to read and she read to me stories from books she managed to get hold of – mainly stories by Enid Blyton which I loved. Milly Molly Mandy was also a favorite. But really, for me, I feasted on comic strips published in the cartoon supplements that came with weekend newspapers – Henry, Dagwood and Blondie, The Katzenjammer Kids and so many more. I do believe that the use of action and body language in my drawing comes from a deep interest in cartooning.

Are there any other children’s book authors that you admire?

Indeed, there are! And I’m afraid most are dead now. But for lyrical prose very few can beat Eleanor Farjeon (1881-1965) the British writer. And I’ve seen no replacement for James Marshal and Arnold Lobel, who both produced children’s books of such charm and humor. I also adore Edward Lear for his nonsense.

But, to be honest, I am now quite out of touch with what’s great in today’s children’s books. But when I do page through publishers catalogues there’s less that catches my eye for what I consider to be truly original. I think cautiousness – a real fear of losing money – and acquiring books through committee decisions has resulted in a kind of cloning of books that are thought to do well in the market. I know I sound like an old fogey, but I can’t help comparing the way in which great children’s books were published in the past – based on the single decision, guidance and vision of those children’s book editors in the past, now legends – Margaret K. McElderry, Dorothy Bryar, Susan Hirschman, Ursula Nordstrom and others.

What is a current trend in children’s literature that you enjoy?

Well, I’ve confessed being unqualified in having an informed opinion. But, while I am not someone who goes along with a kind of foolish political correctness, I do like it that there are now social issues that are being dealt with in contemporary children’s books. And any topic handled well that helps a child feel good about themselves, and certainly not alone dealing with issues that cause them unhappiness, is good to see being explored in children’s books. So issues regarding poverty, race and gender are to be welcomed. But if they are handled badly, that is, when in the hands of a political activist, rather than a writer, they offer no more than thinly disguised manifesto, which are to me a simply horrid.

What is the most difficult part of writing children’s books?

Making a few words mean a lot. And humor; you can learn to craft your writing but no one can teach you how to be funny.

Do you have any suggestions for writers going into the children’s book genre? Or fiction in general?

Use your children’s library as your laboratory, starting by studying the physical make up of a children’s book ( I used to do autopsies on second hand children’s books to see how they were put together). Acquire a critical faculty so that you begin to understand what makes certain books work and others, not. I talk as a writer and illustrator, so the same applies to young illustrators. Also, don’t only study new publications, include great works of the past.

What do you suggest to parents who are trying to get their children to read more?

I assume that parents who want their children to enjoy books enjoy books themselves – and that’s a good way to encourage reading by setting an example. Libraries, these days, are fun; made so by librarians who are my favorite people because I have never met a librarian who does not have sparkle and an infectious enthusiasm for engendering a love of books in children. They are angels in their ability to guide a child to exactly the book they need at whatever stage they are at. So, make visiting your library with your children a regular event. I encourage working parents to ignore the terrible news on TV when they return home from a stressful day’s work. Kick off your shoes! Sit side by side and read to your child. Journey together through a story that connects both you and child to your inner selves – this is true bonding.

Educators regard literacy as the cornerstone of all learning and progressive parents appreciate the importance of reading in terms of their children’s education. However, fewer parents appreciate the deeper influence of literature and love of story. That is: the power stories have to transform us, even making us better people as we develop understanding, empathy, respect and tolerance for others as portrayed by fictional characters. In this way, stories, especially folk and fairy tales, help set our moral gauge and prepare us to engage with the world and its troubles.