An excerpted version of this Q&A appeared in our newsletter. Each month, we include things like information about events, giveaways, sales, and fun extras like author Q&As. If you’d like be the first to know about what’s going on at Catalyst HQ, be sure to subscribe!

We’re getting ready for another big release at Catalyst, A Road Called Down on Both Sides: Growing up in Ethiopia and America by Caroline Kurtz (out July 15). It’s big for a few reasons: not only is this our first non-fiction release, but because Caroline is US-based, we’re able to help her plan a few events in support of the book. What this means for you book-lovers out there, is that you may get a chance to see Caroline in person as she talks about her memoir detailing her life growing up in rural Ethiopia in the 1950s. She’ll be holding a book launch at Annie Bloom’s in Portland on July 15.

We’re getting ready for another big release at Catalyst, A Road Called Down on Both Sides: Growing up in Ethiopia and America by Caroline Kurtz (out July 15). It’s big for a few reasons: not only is this our first non-fiction release, but because Caroline is US-based, we’re able to help her plan a few events in support of the book. What this means for you book-lovers out there, is that you may get a chance to see Caroline in person as she talks about her memoir detailing her life growing up in rural Ethiopia in the 1950s. She’ll be holding a book launch at Annie Bloom’s in Portland on July 15.

As the daughter of Presbyterian Church missionaries, Caroline and her family packed up their lives in Oregon, and headed to Maji, Ethiopia. It was during her time there that she discovered what it was like to live between cultures. She came of age in a country that felt as much like home as her native country, and yet, she was outside of it. When she returned to the US, she again felt like an outsider. In this thoughtful memoir, Caroline explores what it’s like to search for home when that means so many (often conflicting) things, how her parents’ faith wasn’t necessarily her own, and how she found home by building it from all of the pieces of her traveller’s life. Now back in Oregon, Caroline is the co-founder of Ready Set Go Books along with her sister Jane, which publishes books for young Ethiopian readers, and she runs a non-profit that brings solar power and economic development options to women in Maji.

We chatted with Caroline about her book, her childhood, and why she switched from writing about dragons to writing about her life. You can also keep up with Caroline’s development work at her website, and be sure to check out her pictures of her life in Maji and beyond.

Can you tell us a bit about your background?

I’m a “Third Culture Kid” all grown up. The term was coined to cover the children of embassy and international aid workers, business people, missionaries (me), or anyone who is raised in a “host country” not the home country of their parents. There’s a growing group of us now, with global business expanding. As children, we TCKs absorb some things from our parents, and some from the surrounding culture. We shape it into something that doesn’t quite fit with either original culture. We have a knack for finding each other in a crowd, and when we do, the shared experience of not quite belonging anywhere but in the middle bonds us, even if our childhood host cultures are on opposite sides of the world.

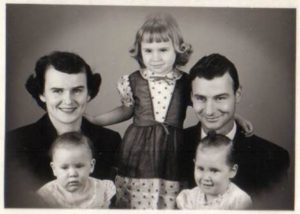

I was born when my dad was in seminary, and before I turned five, he took our family to Ethiopia with the Presbyterian Church. I went to boarding school from fifth grade on and came back to the US for college—a culture shock much bigger than the one I don’t even remember, arriving in Ethiopia. I had a checkered adult career experience until I returned to teach in Ethiopia in 1990. I discovered that’s where I still felt at home, and I’ve been running back and forth ever since. The joy is that I get to participate in both of my cultures regularly. The grief is that when I’m there I miss here, and when I’m here I miss there.

What made you want to tell your story in a memoir?

My dad was a story teller, and I’ve always entertained friends with stories from my exotic past, so in many ways, memoir was a natural for me. I tried fictionalizing a few stories when I was first experimenting with writing. I also tried writing for young adults or middle-school age young people. A writer friend, Susan Fletcher, who wrote a series of dragon stories, said of my dragon story, “If I’d grown up in Ethiopia, I wouldn’t be writing about dragons!” And my sister, a published author of children’s and middle-grade books said about my first Ethiopia book, “The good news is that this is well written. The bad news is that these are adult themes!” Between the two of them, they guided my path to adult memoir.

Can you talk a bit about what the process is like as a first-time author?

Can you talk a bit about what the process is like as a first-time author?

My process as a first-time author was a really long one. I’ve probably rewritten this book four times, from start to finish. I took long breaks from the heartbreak of starting over. My interesting and challenging life has sometimes been more interesting to me than writing about it, and I’ve laid the book aside. But I’ve always come back to it. I’ve been motivated in one sense by the drive to tell my story, but sometimes just by the stubborn desire to master the challenge involved!

I wrote and rewrote scenes; I wove them in, I took them out, I darned over the holes. I rearranged the sequence of present-time moments and flashbacks over and over. That’s on the grand scale of the book. On the smaller scale, it took me years of practice to get to sentences that didn’t sound like someone else, or that didn’t sound like your fifth-grade social studies teacher (when I was writing about the history of Ethiopia). I learned that I had to love the process. If I hadn’t found joy in working with words, even words I had tried before, I would never have kept working.

The original manuscript went on to follow my family to Kenya and South Sudan, where I worked for another four years. Late in the process, Jessica, my editor, suggested we make my first book a “love song to Ethiopia,” and hold the rest of the material. That meant I had to reshape the emotional arc, and bring forward the sense of having reached some resolution in my journey between two cultures. I wrote a lot of new material in the last couple of years to wrestle that arc to ground.

I have shared my work, as often as I could produce newly written or revised pages, with a group of smart and dedicated writers. Some of us have been meeting weekly for almost 20 years! Even when we run dry personally, we show up to share our smartest story insights with those the muse is blessing. Without these friends—that’s you, Lily, Susan, Barbara, Martha and Raina!—I’m doubtful I would have found the strength to keep going over so long a time.

One through-line in your book, in addition to your unusual childhood, were some very universal things—particularly around gender. Did you feel like you were writing a feminist or political book? There are also some very interesting aspects about mother-daughter relationships in there. Was it difficult to revisit some of those moments in your life?

My mother died just over a year ago, and my siblings and I jointly managed her care in her last ten years. She had been, as you’ll see in the book, a witty and energetic extrovert. Dementia washed away all of her sparkly personality, leaving her silent and unsmiling. In the end, not even communicating. The transformation in Mom gave us all a hunger to figure out who she had been—what kind of mother she had been to each of us. Those conversations helped me craft a more balanced picture of Mom. I might have otherwise over-emphasized her as a demanding mom who put unfair burdens on me, as the oldest daughter. She did do that, but she could also be fun, one of us girls, when we were teenagers and Dad was traveling. She was smart and witty, and she loved it that we were smart and witty, too.

That brings me to the question of writing a feminist or political book. I didn’t set myself to do that, but it’s no surprise that you would see a thread about female strength in my book. Though Mom never worked a paying job, she also never fit the stereotypes of a 1950s stay-at-home mom. Before they married, she rode behind Dad on a big, formerly police, motorcycle from Illinois to Oregon and back! For a while in Ethiopia, Dad flew a small single engine plane to bush airstrips around southern Ethiopia. Mom often put my youngest siblings into boarding school and flew off with him. After they retired to the US, until they were in their 80s, they traveled together to China, India, Romania, Turkey, Egypt on mission project trips. Without hoisting a feminist flag, Mom was a model of someone who lived the life she wanted to live and did the things she wanted to do. Isn’t that one definition of a feminist? Mom’s home was always overflowing with books. She had a poster in the kitchen: Spiders relax! I keep house casually! She finished up her BA in literature from Portland State University when she was in her 60s (and walked across the stage just after with my youngest sister). She finished college and went on studying Spanish just because she wanted to. She was no shrinking violet herself, and she and Dad were proud of their girls’ spunk and wit.

But to write a memoir, a person has to be willing to admit their mistakes, something that’s hard for me to do. Difficult moments of writing came less when I was writing about being a daughter, and more when I wrote about being a mother. I had to face the reality that for all my resentment toward Mom, who was not a cuddly, nurturing mother, I turned out to be the same kind of mother: rather businesslike, unempathetic—and also capable of being fun and witty! My daughter once said, at about age 15, “Why can’t you just dote on us?” I am now a recovering “doter,” practicing on my grandchildren. (Which may irritate my children all the more!)

Building on that, memoir writing requires, by necessity, for a writer to dig deeply into their past. How did you approach that process?

Death to a memoir is coming at the events of your life from a defensive position, hoping to justify all that you felt, thought and did. What we want instead, when we read a memoir, is to see the frail heart of another human being. We want to know: how did she overcome? How did she use the bumps and bruises of her life to become tender? How different she is from me! At the same time, how like me!

Even theoretically knowing this about my project, I managed to slip in plenty of resentful, entitled outrage over the knocks on the head that my life sent. I owe it to the kind but uncompromising feedback of friends in my critique group for rooting out those moments and sending me home to plumb my heart for a more generous, humble spirit.

I also belong to an analytical group of siblings, and we love to talk about the complex dynamics in our family of seven children (one of whom died as a baby, and has added to the complexity in his absence). Because my writing process spanned the last 20 years, the emotional work took place as we all moved into that middle age mode of reflection on life. Over those years I renewed my relationships with my adult siblings, and I watched my children become adults and comment on my parenting. It is a humbling process, life. So, I believe my writing practice and my dedication to growing wiser fed each other.

Do you have any advice for writers who’d like to write a memoir?

Much of my advice to beginning memoir writers is slipped between the lines above. I would add this: do tell your story if it’s bursting out of your heart. If it’s not insisting, if it’s not giving you any rest, the process may beat you up too much. So, if you have to write, or you can’t explain why but you just want to, give yourself time to discover and rediscover the real story—not the events, but how you felt and reacted to the events. Be prepared to be humbled as you find that inner story, because it won’t show you to be the “model child” (as I was dubbed). And know that, the closer you can come to the bone of who you are, a flawed miracle, the more we will give you the tender grace we long for ourselves—we will like you better if you’re not perfect.

And more practically, be prepared to learn more about writing than you thought possible! You have to learn the craft of finding evocative words, making pleasing sentences and gathering them into paragraphs in the right order. That alone, is harder than you think.

Then there’s the emotional arc, that elusive emotional arc—what was I like when I started out, what happened, and what did I make of it? All the while moaning to yourself that you’re not dead, you’re still in formation, how can you say what you learned from life when you’re still learning?

You’re writing both inside and outside of cultures, which can be tricky. How do you handle writing sensitively about a culture that’s not inherently yours (but may very well feel that way, or has become part of yours) and how do you write about a culture that you have been a part of but are critiquing in some ways?

In many ways, that’s been the challenge of living my life, not just writing about it. Just before this book went to the publisher, I realized I’d unfairly represented the history of one of the ethnic groups of Ethiopia. I am so grateful to the Ethiopian readers and friends who read an almost-final copy and pointed this out. For a month, I had a stack of history books teetering on the footrest of my big easy chair as I went back to research again.

But even the friends who challenged me said this book shows my love for Ethiopia and Ethiopians. Their words show that the real trick is not a trick at all. Because being someone who writes sensitively is like being a “woke” human being. Your heart is going to show. If you’re a cynic, your hard heart will show up in your writing, no matter how you work to hide it. If you have a mean streak, there will be a moment in your writing where we, as readers, will say, “Ouch.”

And so, writing sensitively about my two cultures came from learning to love them both. Once I had that love, the thoughtful words followed. And that love gave me the humility to hear criticism and to keep growing until the love could glow on the page. I hope, anyway, that my love for Ethiopia glows on the page, and that I have also learned to love the culture that was actually harder for me, the one I never really lost in spite of all my years away, here in the US.

What do you hope readers take away from your book?

I hope readers feel a thrill in meeting Ethiopia, similar to the feeling we have when we meet a person we can tell we’re going to love. I hope there are also some smiles of rueful recognition from persons who were mothered and who have mothered. Also, I’ve had Jewish friends comment on how my struggle with “fit” mirrors theirs, for all the fact that I’m a born and raised Presbyterian. Many of us don’t feel a “fit,” whether in our families, the ethnic make-up of our neighborhoods, the beliefs or values of our cultures. I hope there are readers who come away thinking, “Wow, I’m not alone.” There are many ways not to fit, and many ways to work it out.

What’s next for you?

As I said, this was once a book that included four more years and two more countries! That story is calling to me now. And again, the emotional arc will be the elusive thing—where was I in my life journey, when I arrived in Nairobi, Kenya to work with Sudanese who had taken refuge from their 30-year civil war? What did I learn, being the only white person, and often the only woman in training teams? How did it change me as I flew into war-torn South Sudan and especially, as I had the luxury to fly back out? I know what happened—many strange and wonderful things happened—but the “trick” will be to distill out what I made of it, and what is universal in how I struggled, was humbled, and in the process became more tender and wise.