If you’ve been following along with us this week, you’ll know that in our panel on December 6, the question of the “Black Panther effect” came up. Simply put, this is the rising tide lifting all boats theory, in which the tide is the raging success of the Marvel films and comics, and the all boats is every other African creator. Needless to say, the effect of Black Panther, in all of its forms, had its pros and cons.

One of the pros is that people from all over are finally listening to the stories African creators have been telling for generations.

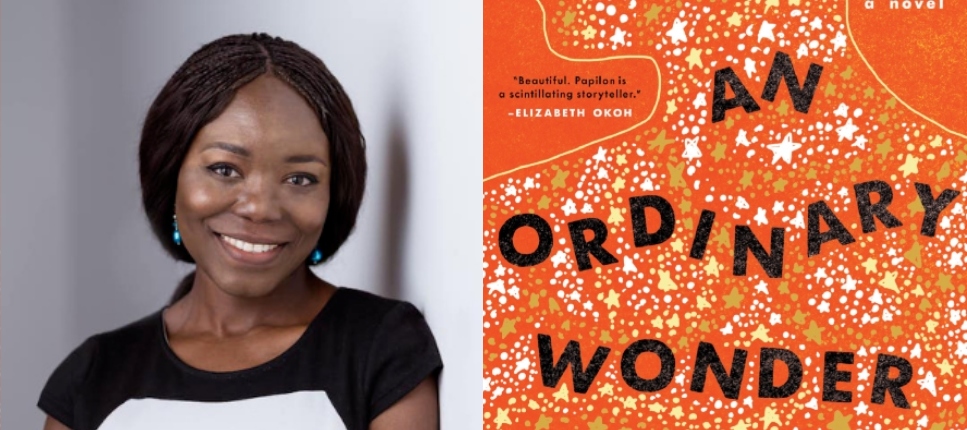

In this #ReadingAfrica guest essay, author Buki Papillon explores what it means to tell your stories and to have those stories heard.

My novel, An Ordinary Wonder, centers on an intersex person who, tossed between a mountain of misinformation and a vacuum of facts about her body, looks to the mythology and folktales and proverbs of her Yoruba heritage for a place to hide her hurting heart and a way to make things make sense. The balm of seeking wisdom from the ancients, of seeking to see and perhaps be truly seen through the lens of what has gone before is particularly potent in difficult times. It is why we turn again and again to the stories that made us, those generations-handed-down myths that help to ground us. In having this, Otolorin is fortunate. Because what if that lens has been stolen and replaced with something that reflects nothing like yourself? Or worse, returns to you a warped and manipulated image that you mistake for the truth?

And so we need reference points for all of this. We need to know what enabled our forbears to survive this mad gauntlet; this unpredictable race from cradle to grave that equals human existence. And the most precious heritage they have left us is stories. We look to stories because that is what remains after the ancients have gone. That is the foundation upon which we can build. In a LitHub chat with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan of the Fiction/Non/Fiction podcast, I shared my belief that we are creatures who exist at the juncture of myth and imagination. What this means is we are continually discovering and reinventing the entire canon of what it means to be human, and what our story is. Take as examples the invention of specific clan tartans by Scottish people. Or the myth of the Golden Stool that descended from heaven to unite the Ashanti of Ghana.

The young son of a good friend once asked me why did such sad and terrible things have to happen in stories. I think I replied along the lines of: well, the earliest humans had to have an unmistakable way of communicating stuff that helps you stay alive, e.g. “don’t eat the berries from this red-berry bush. They will kill you. They do, unfortunately, look exactly like the berries from this other red-berry bush that will heal you. Difference is one of them has slightly furry leaves.” Later, dazed and confused after running miles to escape a saber-tooth tiger, early human you might collapse in front of a berry bush desperate for sustenance but not remembering which berry is safe to eat. Then you remember that night weeks ago, sitting around the fire outside the cave, the day’s hunting and gathering done and the shadows growing long as the night sounds fill your ears, making you glad of the safety of the tribe. You remember the story the old Griot told, a myth about how the day god and the night goddess quarreled because the day god was beginning to favor a young star over her. And so the night goddess set out with a cunning plan. She secretly fed the young star the red-berries of this bush and the young star fell to earth, became mortal and died. But with her last divine breath, powerless to harm the night goddess, the young star cursed the red-berry bush that had hurt her that its leaves would become furry with poison so that anyone who ate it would die. But the red-berry was sacred to the night goddess so one bush escaped with smooth leaves and those have remained safe to eat. Now this would serve to help you and the entire tribe to remember; smooth leaves – good, furry leaves – bad. In this way, stories and myths save our lives and preserve our existence.

People of African heritage have finally entered a new era, one of centering and celebrating and sharing with the world our mythologies and stories and art from our own ways of seeing.

But, as Octavia Butler so aptly opined, humanity’s greatest woes arise from the fact that we are hierarchical creatures. Thus in order for one group to declare superiority and seize power, they must destroy or suppress or otherwise obliterate the stories of those they want to dehumanize or rule over. Removing a person’s story or their myth is a potent act of erasure, sometimes right down to silencing language – the primary vehicle of stories. Subtle and unsubtle methods have long been employed to depict African traditions and myths (from the vantage point of the Western gaze) as being other than beautiful and amazing, including the deliberate practice of referencing them with negative words as a means of suppression and erasure. I am very conscious of the power of words. I recently watched a documentary exploring the life of Toni Morrison and loved a story she told about when, as very young children, she and her sister were innocently copying out a new word (starts with F…) that they had just found grafittied near their home. Their mother saw it and went extraordinarily ballistic. Ms. Morrison, of course had no clue at the time what the matter was and her mother declined to explain. But she never forgot that this was the power of what words can do.

People of African heritage have finally entered a new era, one of centering and celebrating and sharing with the world our mythologies and stories and art from our own ways of seeing. We have always known our faces are beautiful. Our scarifications and our roundness and the soft, soft springiness of our hair are beautiful, as are the broadness of our imaginations and the diamond point sharpness of our intelligence. Above all, our creativity is phenomenal. This is only amplified by the connections fostered by a newly interconnected planet, allowing for the emergence of breathtaking collaborations in art and music and design and so much more. We went to cinemas and read books and were brim-filled with stories and myths of ancestries and heroes that were not ours, and reflected nothing of us. When they rarely did, it was only steadfastly from an outside view. But now, artists of African ancestry who have for too long been cut off from one another and from the stories needed to create from within their own myths from within their own gaze, are now collaborating and drawing from the deep endless well of their joint heritage to create stories and canons that fascinate and rivet and are as powerful and relevant and important for all of humanity as anything that has gone before. I particularly enjoyed reading about how visual artist Laolu Senbanjo worked with Beyonce for her visual album Lemonade, and wove in elements of Yoruba lore using ori body art and Yoruba patterns and symbols.

Human beings are story addicts. We experience our existence through story. This is the tragedy of diseases like dementia and Alzheimer’s. The entire story of a self is eventually lost to its owner, and so they still exist but also no longer are. Story keeps us alive. This is why erasure has been one of humankind’s most terrible weapons against those who are considered enemies. The names chiseled off Egyptian stelae and obelisks, the statue defaced – to remove their story forever. Or the replacement of a local indigenous creation myth with that of the conquering horde.

I was born Yoruba in Nigeria. I grew up reading voraciously. World myths fascinate me. Yet nothing else gets my imagination salivating, like a cat that heard the can-opener, like the myths and folklore of my origins. One excellent thing that my early Nigerian childhood education did was ground me in stories about and by the people around me. I will never forget the specific moment in Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe that broke me—left me stunned and unable to take a full deep breath for a few good seconds. For a time, as I grew up and away from home, I bought into the hoodwinking that I had to set aside the things that mattered to my great, great ancestors in order to be properly ‘modern’ and ‘educated’. But then I began to remember and as I did more research, I found myself awed.

Story keeps us alive. This is why erasure has been one of humankind’s most terrible weapons against those who are considered enemies.

In the last few years, so many books are bringing readers to fantastical worlds based on African inspired myth and lore; The Gilded Ones series by Namina Forna, Children of Blood and Bone series by Tomi Adeyemi. I will read anything Nnedi Okorafor writes and I am still hoping Remote Control will have sequels. And there’s Marlon James’s Black Leopard, Red Wolf. Ben Okri’s The Famished Road. Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater, Saraa El-Arifi’s The Final Strife. And so many more. Young me would have been ridiculously thrilled to see all this. I was deeply into fairy tales and fantasy and myths as a child, yet the fantastical creatures I saw in books represented nothing like me. Now I avidly enjoy images that depict people of African ancestry in all of our glory as beautiful mythical or fantastical creatures, our styles of clothing and body ornamentation and so much more imagined into fabulous futuristic or fantastical settings. The recent proliferation of African literature-inspired movies and series on outlets like Netflix has been incredible, too. I hope young people worldwide help themselves voraciously, especially those of African ancestry. I loved Death and The King’s Horseman by Wole Soyinka and there is apparently a new film out on Netflix, based on that play, titled Elesin Oba. I can’t wait to watch it.

I loved the Dora Milaje in Wakanda Forever! Otolorin, the main character in my novel, An Ordinary Wonder, would have thought she’d died and gone to heaven if she walked into a movie theater and saw this incredible representation. In An Ordinary Wonder, one of the ways in which Oto draws courage in her fight to become her whole self, is to imagine being warrior Queen Amina who lived in 1500s, and ruled over the kingdom of Zazzau, present day Zaria in northern Nigeria. Otolorin draws an image of the warrior queen, imagining her charging into battle in her red turban and emerald earrings, wielding a deadly spear. One thing readers have repeatedly told me they enjoyed, which was also one of the joys of writing the book, is that Otolorin has this rich mother lode of myth and tradition and proverbs to draw upon in her quest. In the mythology that I have created around Oto’s story, and based on an original myth, Yemoja is a water goddess who takes on the responsibility of guiding Oto in order to make amends for the actions of her husband, Obatala, the creator of human bodies in the Yoruba pantheon of Orisha.

I for one (and clearly the entire world as well) look forward to seeing more African mythology and folktale-inspired outpourings forged from the legacies of the Black Diaspora. I have the delightful feeling that things are just warming up, and can’t wait to see what creative wonders the future holds! Representation matters. Our stories make us. Our Myths R US.

Buki Papillon was born in Nigeria. She has a Law Degree from Hull University in the UK, and an MFA in Creative Writing from Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her debut novel, An Ordinary Wonder, has received rave reviews and mentions in the New York Times, Ms. Magazine, Essence, Cosmopolitan UK, YNaija, and more. An Ordinary Wonder is also a Maya Angelou Book Award Finalist, a Massachusetts Book Awards Fiction Honors Recipient, and a Ferro-Grumley Literary Award Finalist. It is brilliantly narrated in audiobook by film and stage actor, Adjoa Andoh (Lady Danbury in Bridgerton).

Buki Papillon was born in Nigeria. She has a Law Degree from Hull University in the UK, and an MFA in Creative Writing from Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her debut novel, An Ordinary Wonder, has received rave reviews and mentions in the New York Times, Ms. Magazine, Essence, Cosmopolitan UK, YNaija, and more. An Ordinary Wonder is also a Maya Angelou Book Award Finalist, a Massachusetts Book Awards Fiction Honors Recipient, and a Ferro-Grumley Literary Award Finalist. It is brilliantly narrated in audiobook by film and stage actor, Adjoa Andoh (Lady Danbury in Bridgerton).

Buki is an alumnus of Key West Literary, Vermont Studio Center, Fine Arts Work Center, and Vona Voices residencies and workshops. Her work was published in Post Road Magazine, Aunt Chloe, and The Del Sol Review. She has in the past been a travel adviser, events host and chef. Buki currently lives in Boston, where she is resigned to finding inspiration in the long winters.

In her downtime she loves taking long rambles in nature, making jewelry, cooking up a storm and, of course, epic levels of reading.

Her twitter account is @bukipapillon. Her website is https://www.bukipapillon.com/