Note: We are the publisher for the South African release of the book. For US purchases, please visit Glynnis’ author page on Amazon.

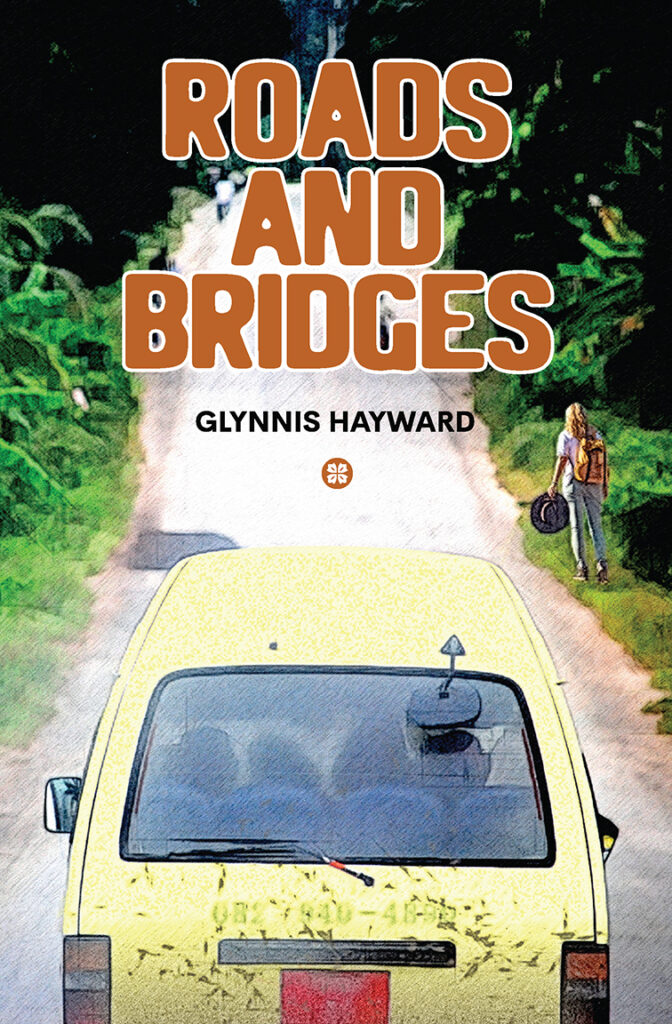

We’re thrilled to team up with author Glynnis Hayward to distribute her newest novel, Roads and Bridges, in South Africa.

Glynnis, a Pulitzer Center award-winning writer, was born and raised in South Africa. After graduating from the University of Natal in KwaZulu Natal, she taught English before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1970s. Roads and Bridges, which follows an American Peace Corps volunteer in South Africa as she attempts to adopt a young orphan and falls for a local man, is her fourth novel. Her first three—A Telling Truth, A Significant Test of Blood, and Light on a Dark Secret—are all set primarily in South Africa and California.

Before Roads and Bridges’ November 1st release, we caught up with Glynnis to chat about being an expat, opening oneself up to others’ truths, and navigating the many liminalities—cultural, emotional, and spiritual—explored in her new novel.

SarahBelle Selig: Glynnis, you’ve lived away from home for a long time. Tell me about what it means to you to be an expat living in the USA. How did your experiences inform the writing of this book, particularly the section when Jabulani and Father Dlamini, both South Africans, visit California?

Glynnis Hayward: I left South Africa during the dark days of apartheid. My husband was offered a job in California and we decided to take up the opportunity. It was not a decision taken lightly as my roots in South Africa are long and deep, but the future seemed bleak in the country at the time. Violence, injustice, and conflict were a way of life and we felt powerless to bring about positive change. But emigrating was painful. Despite speaking more or less the same language, everything seemed different and strange in California. People were extremely kind and welcoming, but my homesickness was almost terminal.

I had been fortunate enough to meet Alan Paton when I was an English teacher in South Africa. At the time, my students were studying Cry the Beloved Country. It was the opportunity of a lifetime to meet the author at a function I was attending and we chatted for some considerable time. He shared an experience that he described as his inspiration for writing the book. He was in a cathedral in Trondheim, Norway, overcome with homesickness, and as he sat staring at the rose window, his thoughts turned to Ixopo where he had been a teacher, and Cry the Beloved Country began to take shape in his mind. I was struck by his intensity and his willingness to express his feelings; but I was amazed because I had also taught in Ixopo, and had also once been in that Trondheim cathedral, staring at the same rose window, and feeling a miserably long way from home.

I was acutely aware of, in the early days of living here, how different I was. We spoke more or less the same language—though I continue to discover differences in vocabulary usage to this day—but it was surprisingly a very different culture. This was reflected in countless ways, and I found it exasperating to be explaining myself at times. Over the years, that acute sense of being different has subsided, but I knew how Jabulani and Father Dlamini would feel. I knew it would be even more difficult for them because their culture and language were more different than mine had been.

SB: On that same train of thought, you’re a South African writing from the point of a view of an American—but as an American myself, I see such authenticity in Mandy, your main character. Tell me about the process of imagining the history, the prejudices, and the fears of someone with such a different background to your own. How did you manage it so well?

GH: I experienced my own children’s reactions, having been raised in America, to working and studying in South Africa. They taught at a pre-school for Zulu children during their summer vacations, and worked at the Institute of Race Relations. My son also studied at University of Cape Town for a semester abroad. In addition, my American godson traveled to Africa with us several times as a child, and later joined the Peace Corps to work in Namibia for two years. I heard many stories from him and learned a lot about his feelings of both self-worth, yet also his sense of isolation being so far from home. Much of all of this went into the creation of Mandy.

SB: You explore South Africa’s many disparities in this story, not just between races and cultures, but between the ancient and the new, faith and despondency, beauty and violence—and in the case of Mandy, emotions that seemingly contradict each other as she attempts to navigate this complicated terrain. Can you comment on that?

GH: Roads and Bridges explores many contrasts. Among other things, it examines the simplicity and complexity of life in South Africa, where modern technology and ancient superstition live side by side; affluence, poverty and race relations in South Africa and California; the comparison between traditional Zulu ways and a younger, less traditional generation; and the unshakeable faith of some characters against the disregard of religion from others. Many of these differences begin to reveal themselves to Mandy that first afternoon as she listens to her companion’s stories. And in transition herself, Mandy begins to change from being despondent and self-absorbed, to feeling concern for others and having a positive sense of what she can do. But she has a lot to learn still.

SB: Mandy really goes up against her community in order to follow her heart and adopt Jabulani, and as the reader, it’s tough to decide whether or not her determination shows courage, hubris, or a bit of both—which feels precisely the point. In your personal experience, where is the line between being receptive to the input of the ones we love, and trusting our own instincts? When is it necessary to listen, and when is it necessary to stop listening and live by your own truth?

GH: Mandy’s wish to help the child was a noble one, but it was this very nobility of purpose that blurred her vision. However, I don’t know that she could have done anything differently. If she had merely listened to input from others and acted on that advice, she would not have shown any strength of character. The trouble was that she wasn’t prepared to pay attention to what anyone else said—she only wanted to hear her own thoughts given validation. In my experience, it’s important to listen to, and consider, the opinions of people you respect, but ultimately you have to do what you think is right. Mandy had to bring Jabulani to California to see how things played out—but ultimately it was hard to face the fact that this wasn’t the best thing for him because she had not allowed for that to be a possibility. The climax of her growth came when she was able to relinquish her fixation about bringing JJ to California and entertain other options. She was able to let go of her own grief and frustrations as well, and look forward.

SB: The taxi scene is the focal point around which Mandy’s journey over the following years revolves. You write so intimately about the characters in that taxi and the lives they lead—they are each dynamic and incredibly compelling, almost meriting a sequel for each of them (can we make this happen?!). It begs the question: where is the line between fact and fiction in the text? How many of these characters are based on people you grew up with in South Africa and true stories from your community?

GH: This book went through many metamorphoses. It started out as a collection of short stories told by travelers, stranded when their taxi ran out of petrol—a sort of Canterbury Tales set in rural KwaZulu-Natal. The stories themselves were all based on stories I’d heard growing up in Africa, both in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Storytelling is such an integral part of life there. The characters themselves were all fictional (other than Mrs. Liz), but they were a collage created from people I’ve known. And the stories, no matter how strange, were based on events that actually took place.

Jessica [Powers, Publisher of Catalyst Press] channeled me in the direction of moving away from a collection of short stories, to the novel that it now is. It became more compelling to have Mandy as the protagonist, finding herself in a situation where she was thrown together with a group of people and forced to spend time with them. Once I had made that switch in focus, everything pieced together much better, although I still have the deleted stories on a back burner and they might reappear at some stage!

SB: Sign me up for that! Alright, last up: the obligatory “what’s next for you?” question. Tell us what your creative plans are for the next few years. Are you at work on another novel?

GH: Well, I have completed the rough draft of a new novel. Whereas Roads and Bridges took many years to complete as it went through its various metamorphoses, my new manuscript The Photograph took less than a year. It stands alone and is not a sequel, but some of the action in Roads and Bridges is seen in it. In it, one of the minor characters in the former book, Joanna Nel, is a protagonist along with her mother, Petra. Joanna’s relationship with Ryan Thompson from Roads and Bridges also takes off. Editing the manuscript comes next and that takes a long time.

—

Roads and Bridges will be on sale November 1st in most South African bookstores. If a copy is not available at your local store, please request them to order from orders@proteadistribution.co.za.