Today, I have the honor of chatting with Bridget Pitt, the author of Eye Brother Horn, which we have the privilege of publishing here at Catalyst Press.

An activist, a critically-acclaimed author, and a fascinating conversationalist, Bridget’s newest novel is an evocative look into the history of colonial South Africa as seen through the eyes of two young boys—Daniel, the son of white missionaries, and Moses, a Zulu orphan abandoned on a riverbank—who are raised as brothers on the mission of Umzinyathi in Zululand. I’ll never forget the first time I read this book, and I know you won’t either. To get you started, be sure to visit Literary Hub to read an excerpt from the novel.

In this chat, Bridget and I discuss the meaning of nationality, her literary influences, how she discovers the voices of her characters, and so much more. Let’s get started!

SarahBelle Selig: Hi Bridget, thanks for joining me! I’d love to start with you telling our readers a bit about your writing background. You’ve definitely seen some great success in your early forays into fiction, with your first crime novel being shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize in 2011, and for the 2012 Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa. But you were also an outspoken environmental and human rights activist in South Africa for many years, and actively spoke out as a journalist against apartheid policies. In what ways is this new story a continuation of that work? How does writing fiction feel different to you, and within fiction, what genres appeal to you?

Bridget Pitt: Eye Brother Horn is my fourth novel, and my first foray into the historical fiction. My first and third books were literary fiction, with the second straddling crime and literary fiction. I realised when writing this book that I was not cut out to be a writer of crime fiction, although I occasionally enjoy reading it. But as a writer I am more compelled by the motivations and the relationships of the characters, and by the unraveling and re-knitting of people’s lives that follow acts of violence, than by how a crime is solved.

For me the spark of a novel may be a character, a relationship, a story, or just a place … the seed for my third novel was a burnt-out hotel in the Drakensberg mountains. Literary fiction allows for the greatest flexibility in weaving these elements into a narrative.

I have co-authored one non-fiction book, a memoir and spiritual reflection of a wilderness guide and friend, Sicelo Mbatha, and a commissioned book on urban nature conservation. I found it both soothing and constraining working within the boundaries of non-fiction after the lawless expanse of fiction. If the right project popped up I’d be up for writing more non-fiction, but even when working on non-fiction assignments I find myself turning everything into a story.

My own activism has always been strengthened and inspired by fiction written with a critical social lens. Story telling is inherently transformative, and can be a powerful medium for advancing insights, provoking questions, and catalysing change. Writing fiction enables me to explore some of the nuances and complexities of social transitions which cannot easily be conveyed in polemical nonfiction. My writing and activism breathe life into each other, although I am acutely aware of the need to trust the reader to draw their own conclusions, rather than driving social points for home with a sledge hammer.

SS: I know you looked into your own family’s history in the research for Eye Brother Horn. You were born in Zimbabwe, raised in South Africa, but you have European ancestors. What do you consider your nationality? What does nationality mean to you?

BP: The Nigerian philosopher Bayo Akomolafe tells us that the human is not a thing within a territory, the human is a territory. Nationality, in the sense of the country where you hold citizenship, is one of many forces that shape our inner ‘territory’. But it’s a continuously evolving and intangible force, and the compatriots of a country as contested as South Africa doubtlessly hold wildly differing ideas of what their nationality means to them.

Like all humans, I am a territory with an entanglement of many different geographical and cultural reference points. I grew up with my eyes turned north – three grandparents had immigrated from England, one was a third generation South African. I was raised on A. A. Milne, Frances Hodgson Burnett and Mark Twain. I knew about the renaissance, the impressionists, the cubists, I listened to Rachmaninoff and the Rolling Stones. My father fell in love with Italy when he was stationed there in the Second World War, and took me there at the age of 13 to marvel at the wonders of European ‘civilisation’. My maternal grandparents were quintessentially English, offering afternoon tea and scones to be taken while flipping through back copies of the London Illustrated News featuring photos of stocky Royal princelings in tweed jackets (I envied them not because they were royalty but because they seemed to have unlimited access to ponies).

I was not given the benefit of learning an indigenous language other than Afrikaans, although I tried to pick up isiZulu at the lively gatherings hosted by our family housekeeper in our backyard. The little South African “history” I was taught at school was a grandiose and tedious fantasy about God helping the Boers and Brits to defeat unruly local tribes. I knew almost nothing of African art, music, mythology or beliefs.

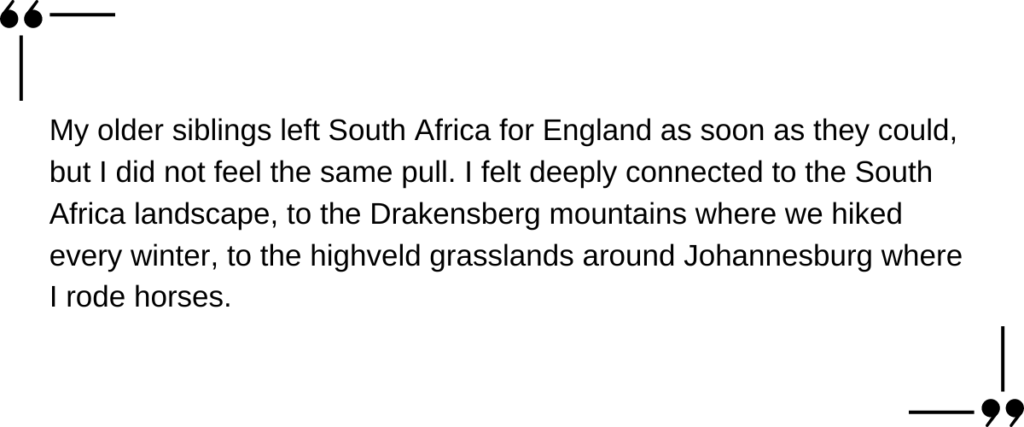

My older siblings left South Africa for England as soon as they could, but I did not feel the same pull. I felt deeply connected to the South Africa landscape, to the Drakensberg mountains where we hiked every winter, to the highveld grasslands around Johannesburg where I rode horses. I went to university in 1976, and soon became immersed in the anti-apartheid struggle. What drew me was not only a strong belief in the cause, but also for the first time in my life I could interact with my fellow black South Africans as comrades. Of course, there was much complexity in that relationship, and my comrades were quick to disabuse me of any feelings of arrogance or tendency to patronise that came with growing up as a white person in apartheid South Africa. This experience was profoundly transforming, and strengthened both my connections to the place and its people, and my resolve to fight for a more just and equal society. Unfortunately, we are still striving to achieve this. But I never seriously contemplated leaving South Africa after this time.

I left Zimbabwe at the age of two and have no memories of it, although I have visited a few times and found it to be a beautiful country with many creative, resilient and resourceful people, notwithstanding successive dictators. My parents emigrated there in 1950 to escape the newly elected National Party and its racist agenda but were forced to return 10 years later due to financial difficulties. When I was a child, I would look at the sepia photos of our house in what was then Salisbury, with its chickens and vegetable gardens, and feel that I had been cheated out of an idyllic youth by being born too late. But the connection was more to some imaginary country home than to the actual place.

So I guess the territory that is me is woven with threads from of many lands, but if I had to choose a single label it would be South African. [Editor’s Note: Be sure to watch Bridget as part of our #ReadingAfrica Week panel, “Who Is African: Place, Identity, and Belonging in Literature” for longer discussion on this question]

Continue reading “Author Q&A: Bridget Pitt”Hot from the Press

Happy new year, Catalyst family! After a wonderful holiday season, we are rested and ready for a big year here at the press—with eight (!!) titles in store for you all in 2023. First up are our two January arrivals, Eye Brother Horn and Pearl of the Sea, which you’ll be hearing lots about on our socials leading up to their simultaneous releases on Tuesday, January 31st. We can’t wait to share these amazing books with you.

Until then, here’s a bit of Catalyst news for you to kick off the year! Our two Panel & Page releases for 2023—Pearl of the Sea and KARIBA—were included on this epic line-up of 2023 African creative projects to look out for from Squid Mag, and our two January releases were also included on this January roundup from the Community of Literary Magazines & Presses. Ameera Patel’s Outside the Lines is the African Book Club’s January book club pick and you can register here for their virtual discussion on January 22nd, which Ameera will be attending to answer reader questions. And finally, check out Pearl of the Sea co-author Raffaella Delle Donne in conversation with Ayo Oyeku on Muna Kalati!

Continue reading “The Spark: The “It’s 2023!” Edition”

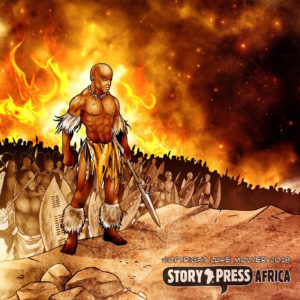

Last month, we launched a Kickstarter to help us fund production and distribution of our upcoming graphic novel King Shaka: Zulu Legend, and we so happy to announce that it was funded! As part of our supporter rewards, we included a buy-one-give-one option that allowed supporters to not only get their very own copy of King Shaka, but to give one to a school or library in South Africa. And through your generosity, the copies you see here will be distributed through our partnership with READ Educational Trust, a South African literacy organization that’s making sure children all over the country have access to books. This is just the start of our work making sure that kids who need books can get them. Your support will also help us roll out a buy-one-give-one option here at our website—so stay tuned! Continue reading “Thank You!!”

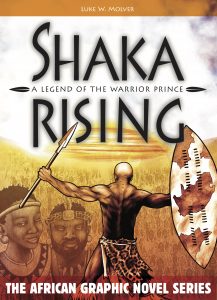

Shaka Rising: A Legend of the Warrior Prince was named an Honor Book for Older Readers by the Children’s Africana Book Awards! The awards, presented by Africa Access, a non-profit that celebrates and promotes African literature for young readers. The Children’s Africana Book Awards are an annual award honoring “authors and illustrators of the best children’s and young adult books on Africa published or republished in the U.S.” We couldn’t be more excited that Shaka Rising was among the honorees!

Shaka Rising: A Legend of the Warrior Prince was named an Honor Book for Older Readers by the Children’s Africana Book Awards! The awards, presented by Africa Access, a non-profit that celebrates and promotes African literature for young readers. The Children’s Africana Book Awards are an annual award honoring “authors and illustrators of the best children’s and young adult books on Africa published or republished in the U.S.” We couldn’t be more excited that Shaka Rising was among the honorees!

Shaka Rising is the first in our African Graphic Novel Series, and the first release from our collaborative imprint, Story Press Africa. You can read about Shaka Rising author/illustrator Luke W. Molver in this Q&A. And you can learn more about the awards, and the other winners and honorees here.

Story Press Africa, our collaborative imprint with South African media company Jive Media Africa, is looking for submissions from artists and illustrators who want to tell the stories and histories of Africa as part of our African Graphic Novel Series.

Story Press Africa, our collaborative imprint with South African media company Jive Media Africa, is looking for submissions from artists and illustrators who want to tell the stories and histories of Africa as part of our African Graphic Novel Series.

The first installment in the series, Shaka Rising—a graphic novel for young readers—told the story of a young Zulu leader’s rise to power against the backdrop of one of southern Africa’s most turbulent times. We want to continue bringing these stories to the page and to readers everywhere. Please read our submission guidelines and get in touch if you have a proposal. We look forward to hearing from you!

Pretty soon, a whole bunch of you will be walking to your mailboxes, and there, tucked between a magazine, grocery store flyers, an electric bill, and all of the other assorted things that show up in the mail these days, will be something we’re super proud of—a copy of Shaka Rising. Through your support and generosity, we were able to fund our Kickstarter project and get started on the next installment of our African Graphic Novel Series. It’s all because of you.

Pretty soon, a whole bunch of you will be walking to your mailboxes, and there, tucked between a magazine, grocery store flyers, an electric bill, and all of the other assorted things that show up in the mail these days, will be something we’re super proud of—a copy of Shaka Rising. Through your support and generosity, we were able to fund our Kickstarter project and get started on the next installment of our African Graphic Novel Series. It’s all because of you.

When we joined forces with the good folks at Jive Media Africa to form the imprint Story Press Africa, it was because we wanted to share all the wonder, the excitement, and the richness of African history and knowledge. Historical figures like Shaka have a lot to tell us about, not just African history, but about our world, and we’re thrilled to share it with you.

A lot of people made this happen. A lot of people cared about sharing Shaka’s story with their kids, their libraries, and their communities and that’s why we made our goal—people like you supported this brand new thing we’ve started. Shaka Rising is the first in a long, long line of African Graphic Novel from Story Press Africa. We’re just getting started and we’re so happy to have you along for the ride.

Thanks for believing in us and the work we’re doing! If you like Shaka Rising, be sure to spread the word! Leave a review on Amazon, Goodreads, your website, or in some sort of elaborate semaphore (if you pick semaphore, please send a video. We’d love to see that). Let your schools, libraries, and community groups know that you got your hands on an awesome graphic novel that’s teaching African history in a fun and accessible way, and that they should get in on it, too. Basically, tell everyone you know that Shaka Rising is here and that because of you, a second installment is on the way.

A big THANK YOU to all of you who donated to our campaign, and be sure to keep watching to see what’s next for us! An especially huge thanks to our partners at Jive Media Africa!

Many thanks to our donors:

Einar Petersen

Mary Fountaine

Emily Dietrick

Ntsike

Anonymous

Erin Subramanian

Jamil Burns

Paul Glasser

Ray “Raytoons.Net” Mullikin

Noel Mills

Chandra Orrill

Shean, Semeicha and Sapphira Mohammed

Robert L Vaughn

Tinsley

Lisa Jensen

In honor of Michael Kromberg

Mary Puthoff

Tessa Moon Leiseth

Peter LaPrade

The Spitzers

Rosie Tullis-Thompson

The Briar Patch

Nate Gillespie

Maureen Babb

Rico Schacherl

The Bells

Mark Gunter

Rachel

Matt Powers

Kathy Shepler

Alberta Jackson

Catherine Ndungu-Case

Assembly of Literatures for Adolescents of NCTE

Derek W.

Matty Sankauskas

Anonymous

Dennis and Becky

Helen Musselman

Edi

Glynnis Belchers

Justin

Kathleen Shannon

Sarah

Scott

Scott Mitchell Rosenberg and Platinum Studios

THE LION’S BINDING OATH