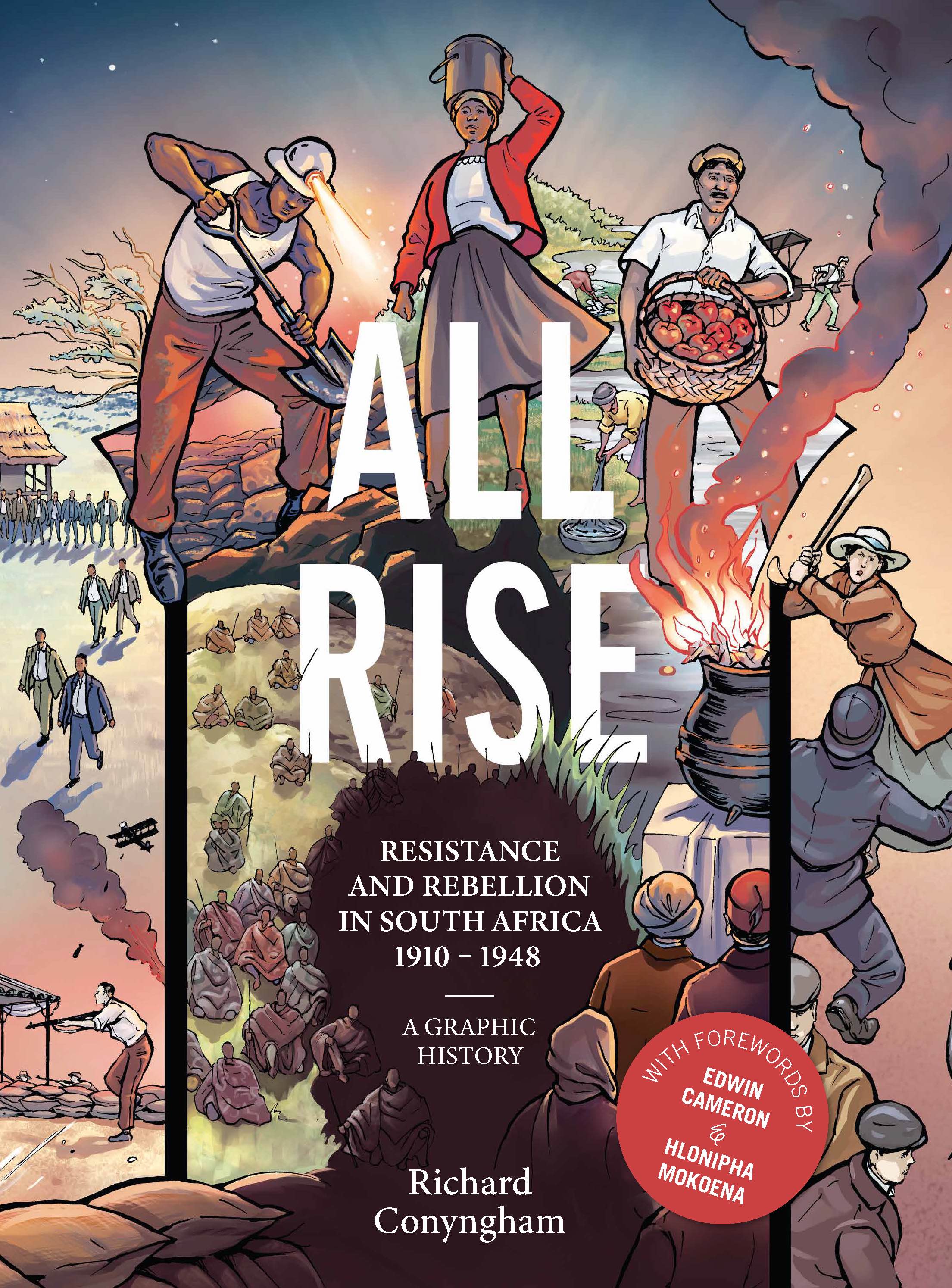

We’re so excited for the upcoming release of All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa, a graphic history of six untold legal cases that shaped the civil rights history of South Africa. Set during the pre-apartheid years, the acts of resistance and rebellion brought to life in All Rise were spearheaded by ordinary citizens from marginalized communities on a mission to improve the safety and freedoms of themselves and their loved ones. Each story is illustrated by a different South African illustrator, creating a visually arresting anthology representative of the vast beauty and complex multicultural history of the “Rainbow Nation”.

I’ve been an observer of this project from afar for many years, so it’s thrilling to see it all come together in print. And today I have the privilege of chatting with the author and historian behind the anthology, Richard Conyngham. Born and raised in South Africa and now living in Mexico City, Richard has degrees from the University of Cape Town and Cambridge University and many years of education and literary work under his belt, having worked with organizations like Equal Education, The Bookery, the London publisher Slightly Foxed, and the edtech organization MakeTomorrow. Back in 2016, he collaborated on his first graphic history with the Trantaal Brothers, an artist duo out of Cape Town (who also illustrated a chapter of All Rise), to create an illustrated companion to the O’Regan-Pikoli Commission of Inquiry into policing in Khayelitsha.

Richard spent the last six years researching and creating All Rise, and all that hard work has paid off to create a truly amazing end result. The collection is getting all sorts of hype from big names in the literary, comics and history worlds alike–including a Starred (!!) review from Kirkus–and we can’t wait to share the book with you when it hits the shelves on May 17th.

Richard, thanks for making time to chat! I’d love to start back at your first graphic history project back in 2016. What did that experience teach you about the medium?

RC: Hi, SB! Thanks for having me. The first thought that comes to mind is a memory from the book launch. It was held at a community hall in the Cape Town township of Khayelitsha. There were about 100 seats, and we placed a copy on each one. The artists and I were standing inconspicuously at the back, and when dozens of local teenagers arrived, sat down and began to leaf through the book, we were able to observe which pages drew them in. Without exception, it was those with illustrations–rather than words–that caught, and held, their attention. It was a clear, convincing display of the medium’s power to engage minds.

“Engaging” minds feels like too small a word for the effect All Rise seems to have on its readers. It’s difficult to read this book and not just take to the streets and make some noise. These stories could inspire the activist in anyone–and they’re also disconcertingly pertinent. What do the stories in All Rise have to say about the power of the individual?

RC: So much of our history has been written in a way that shines light on a few “extraordinary individuals”–both heroes and villains. Even if all of them were extraordinary, this perpetual emphasis on Big Names has also had a distorting effect on how we perceive “ordinary, everyday” individuals, including ourselves. As I hope the stories in All Rise prove, you don’t have to be a gifted orator or even a natural leader to shape your country’s history. In South Africa throughout the twentieth century, there were instances when the law made this possible, even during periods when the courts were largely complicit in the oppression of working-class people, and particularly people of color. This is why I think court records are such a rich source of history–because they are a quiet reminder of the women and men, famous or forgotten, who were brave enough to break the law or to turn to it in the pursuit of justice.

Tell me a bit about your discovery of the court records you used to recreate these stories, because that’s a story in itself. Did you know right away that you’d found something incredible? And how did the idea come about to create a graphic anthology, hiring a different illustrator for each story?

RC: It all began back in early 2014, when I traveled to Bloemfontein with activist Zackie Achmat. Zackie’s intellectual curiosity and his long career in civil-society litigation had brought him in contact with some fascinating, 100-year-old resistance cases that even judges and historians knew little about. So the project began there–in the Supreme Court’s dusty archive, with me tagging along as researcher and co-writer. Reading through those records, I was immediately struck not just by their prescience but also their narrative potential. For me, the characters and events were too ‘visual’ for words alone, so over time I began to explore the prospect of a spin-off graphic history. In many ways this was a much harder path to follow than a traditional, text-only history book, but the idea seemed worth the effort. For the first chapter I collaborated with the Trantraal Brothers, whom I already knew well, but before long I decided that each story was calling for its own unique artistic style. I went on to headhunt five other top local illustrators, always looking to match the story with their interests and artistic sensibility. Diversity felt right, as did the medium, because the end-goal was to produce something that not only revived, and made accessible, six forgotten stories, but also mirrored South Africa in all its color and many-sidedness.

I can imagine it was a mammoth task, administratively and creatively, to manage such a big and diverse creative team, which included yourself, six illustrators all from different artistic and cultural backgrounds, a graphic designer, a cover artist, the list goes on. How did you find a balance between keeping the creative integrity of the illustrators and trying to create a cohesive body of work?

RC: Ha, yes, collaboration comes with its challenges but from the very beginning I’ve always had huge respect for the abilities of every artist who contributed to All Rise, and in return, I suppose I was lucky in that they trusted me with the research and scripting side. Every artist brought their own creative rhythm, and with each one it was important to find room for differences of opinion and process. I encouraged unvarnished feedback on my written narratives because I wanted the artists to catch my weaknesses and blindspots–and fortunately they delivered time and again. In terms of how all of the stories fit together into one cohesive body of work, I think Gaelen, the book’s designer, had a lot to do with this. He joined the project at a crucial moment, guiding many of the finishing touches from cover and title pages to the ‘behind the story’ sections.

There’s a lot of focus–in both the academic and literary spheres–on South Africa’s Apartheid era, but the stories in this book all take place in the years leading up to it, from 1910 until Apartheid began in 1948. You refer to this period as South Africa’s “Union Years”. Do you find that this era of history is neglected? How did it inform South Africa’s apartheid years, and in what ways does it still inform civil rights in the country today?

RC: Very neglected, in my opinion, which is surprising when you realize just how explosive and action-packed the period really was. I remember studying 1910-48 as part of my high-school history syllabus in the nineties. It was extremely dry: dates, party politics and some grainy photos of Smuts and Hertzog–that’s about as much as I can remember. Nothing about washerwomen going out into the night to get arrested, or Indian fruit hawkers getting deported for burning their registration papers, or white miners taking up arms against the state while bombs rained down on them. It’s not that these stories have never been written about before–it’s just that the best books are now unfortunately long out of print. Apartheid does a much better job of capturing the popular imagination, but that shouldn’t be the case because the Union Years are equally significant as a prelude to the country we know today, and the struggles the period witnessed were also no less epic.

These are obviously quite localized stories, but what do you think American readers, and global ones, have to gain from reading the collection? Besides the fact that they’re gorgeously written and illustrated, of course!

RC: I’m sure many international readers will be surprised by the universality of the book’s themes. But I hope that there are also unexpected revelations that challenge readers about South African history and the role of the law in any society. If we tick both of these boxes, and the illustrations motivate readers to persist until the very end, then we’ve achieved our aim!

Finally, tell us a bit about the future of the All Rise project. A little birdie tells me that this might just be the first of many volumes. Can you give us any hints about what comes next?

RC: I’d love to take on a prequel at some point. But who knows, there are plenty more resistance stories out there waiting to be told, both in South Africa and beyond. So let’s see…

All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa is on sale worldwide May 17th and available for pre-order here. For South African readers, you can get All Rise now in most bookstores or online from our pals over at Jacana Media!

All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa is on sale worldwide May 17th and available for pre-order here. For South African readers, you can get All Rise now in most bookstores or online from our pals over at Jacana Media!